Generations once associated Kodak with the magic of capturing memories. From family vacations to festive celebrations, its yellow-branded film packs were household staples. Yet today, Kodak stands more as a cautionary tale than a photography titan.

Despite once commanding a $31 billion valuation, the company lost its grip by ignoring the very technology it helped create.

From Innovation to Hesitation

George Eastman and Henry A. Strong founded Kodak in 1892, and with their fixed-focus box camera, they transformed photography. Introduced in 1888, the original Kodak came pre-loaded with film and cost $25—a luxury at the time. Users could send it back to the Rochester headquarters for film processing for $10, while professionals could simply reload it for $2.

For decades, this business model succeeded. The real profit didn’t come from cameras, but from selling film separately. Kodak effectively controlled how people captured and developed their photos, and that gave the company decades of dominance.

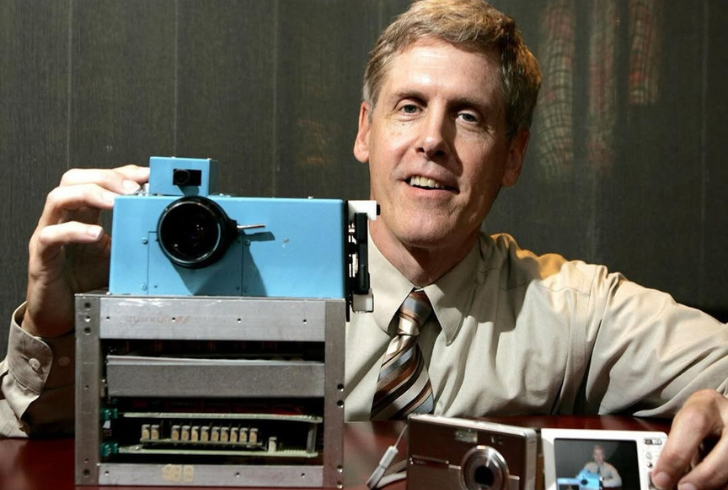

However, a pivotal moment came in 1975 when Kodak engineer Steven Sasson developed the first digital camera. Rather than embrace the future, executives feared it would cannibalize their profitable film business. They shelved the innovation. That decision marked the start of a slow decline.

Delayed Adaptation and Lost Momentum

By the late 1990s, Kodak started to feel the pressure. Rivals like Fujifilm were gaining ground, especially in the digital space. However, Kodak ignored the digital wave until it was nearly too late and continued to rely on its film sales.

In 2001, then-CEO Daniel Carp began shifting the company toward digital photography and printing. Despite this, Kodak was the market leader for digital cameras in the US. By 2005, its margins shrank quickly. The market had changed. Asian competitors were manufacturing digital cameras at lower costs, and Kodak couldn’t keep up. They sold cameras, but often at a loss.

The company scrambled to restructure. Kodak shut down key facilities, outsourced production, and pivoted away from its legacy products. In a painful symbolic move, it discontinued its iconic Kodachrome color film in 2009, ending a 74-year era that had defined much of modern photography.

Lawsuits, Loans, and Letdowns

In an attempt to survive, Kodak arranged a loan of $300 million. However, financial relief proved temporary. The company sold off its profitable health imaging business and became tangled in a web of legal battles, including lawsuits against Apple over patent claims. These efforts didn’t stabilize Kodak’s position.

On January 19, 2012, the company officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The announcement marked a low point for a brand once seen as unstoppable.

The Comeback Attempt

With a new approach, Kodak came out of bankruptcy by September 2013. Instead of focusing on consumer photography, it licensed its name to other companies and positioned itself as a supplier of motion picture film.

This pivot allowed it to retain a presence in Hollywood, where traditional film still held artistic value. Kodak now provides the film stock used in productions like “Oppenheimer” and other analog-loving blockbusters.

Despite two failed attempts at launching cryptocurrency ventures, Kodak has clawed back some relevance—although it remains a shadow of its former self.

What Kodak Couldn’t See Coming

Internal voices tried to warn leadership. Back in 1979, employee Larry Matteson authored a report predicting a shift to digital photography by 2010. He wasn’t far off. Unfortunately, the executives chose to sideline such predictions.

Likewise, Steven Sasson’s digital camera prototype represented a once-in-a-lifetime innovation. Kodak had the talent, resources, and timing—but lacked the vision to pivot. That misstep cost them billions.

Kodak’s story teaches more than just corporate miscalculation. It highlights how clinging to outdated models—even successful ones—can lead to irreversible decline. Innovation, after all, only matters if a company embraces it.

When companies ignore internal innovation and cling to legacy profits, they risk becoming obsolete. Kodak had the tools to lead but chose delay over disruption. That hesitation left a lasting impact—and a powerful lesson for every business chasing the future.